HISTORY FEATURE: When Rotherham built the nation’s most advanced electricity station

The normally purely practical appearance of this “super-station” had been transformed — there was bunting and roses, with an enormous Union flag draped over the centre.

Across the whole width of the building was a broad red strip with yellow tassels, and at the top about a dozen pennant flags were flying in the breeze.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdRed curtains with yellow edging were hung across the main door — and these were swung aside as the Prince of Wales entered.

There was the usual excitement for a royal visit in Rotherham, but the official opening of the “super-station” on May 28, 1923, brought an additional buzz.

The previous electricity station — inaugurated in 1901 in order to power Rotherham’s tramways — was capable of about 200kw at 460 volts.

Our state-of-the-art super-station — the first of its kind — would output 30,000 kilowatts at 6,600 volts. It was enough to meet the entire electrical requirements of a large town back in 1923.

A lot had changed in the previous couple of decades.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe outbreak of war in 1914 amped up the need for further power station development, with unprecedented demand from overworked munitions factories.

So in March 1917, the Ministry of Munitions and Rotherham Corporation signed an agreement to erect what was referred to from the start as a “super power station”.

The colossal power unit comprised a huge steam turbine running at 1,500 revs per minute to drive a large electrical generator.

The turbine and generator — weighing a combined 300 tons — were designed and built in Rugby, Warwickshire, by British Thomson-Houston.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe largest of the turbine’s 14 wheels was 12ft in diameter. Steam was pumped in at a pressure of 220lbs per square inch.

There was little time for speeches as Prince Edward arrived for his tour but there were big cheers at the announcement by Rotherham’s town clerk that the royal had granted permission for the site to be named the Prince of Wales Power Station.

His Royal Highness pressed a switch to declare the place officially open and began his look-around, guided by Edward Cross, the borough’s electrical engineer.

Edward also signed the guestbook, turned the handle which started the machinery and touched another switch which illuminated a large picture of the coat of arms of the Prince of Wales.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn previewing the special occasion, The Advertiser said: “The official opening of such a power station is a ceremony not unworthy of the heir to the throne, for the undertaking in Rawmarsh Road is one of the largest in the country, and electricity is the most potent force that man has succeeded in harnessing to serve his needs.

“It is natural that our Prince should show an interest in the development of a power which will in all probability provide solutions of some of the problems which today baffle industrialists, and be one of the most important agencies for the improvement of the conditions of the manual workers of the land, for whose welfare the Prince is well known to be deeply concerned.”

His day in Rotherham also included lunch with VIP guests at the town hall, a trip to Clifton Park — where he had been scheduled to lay the cenotaph’s foundation stone the previous summer — and an inspection of ex-servicemen in a ceremony also involving units of scouts and guides.

After his visit, the impressed royal contacted Rotherham’s mayor to thank our “busy and enterprising” town for its hospitality.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe royal wrote: “Rotherham has always enjoyed a reputation for progressiveness; and it was in keeping with that reputation that, among the many large electrical power stations in England, the first super-station should have been erected here.

“In districts such as this, the demand for electrical power is naturally enormous — without it, the industrial expansion of the neighbourhood would be seriously hindered; and it was inevitable that this demand should increase after the war.

“It is a tribute to your long-sightedness in Rotherham that you forestalled this demand, and a tribute to your engineers that you have been able to meet it so successfully.”

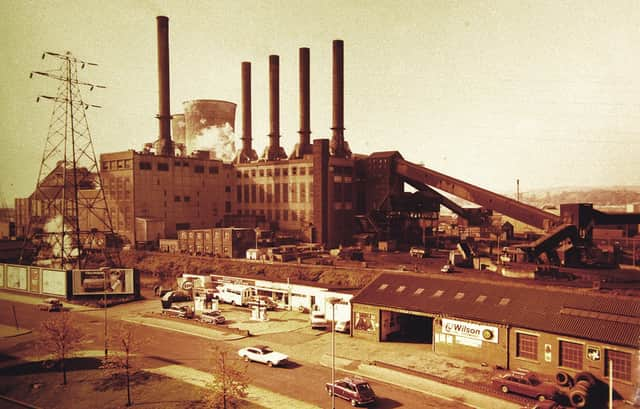

Our super-station generated electricity until noon on Friday, June 3, 1977.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTwo of the four chimneys had been taken down the previous year, and just after Christmas 1976 work started on demolishing the two cooling towers, each of which had a 1.8 million gallons per minute capacity.

Nearby offices and factories meant explosives could not be used so both were manually dismantled until about a third of them was left. The rest was brought down with the classic crane-and-swinging-ball technique.

As the second cooling tower was being razed, the concrete base gave way to reveal a 26ft deep underground lake.

Tests showed the water was clean, and it was suspected that it had gathered from the cooling process rather than leaked from elsewhere.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis was pumped away into the river and, by summer 1978 there was nothing of the towers left on the site.

When Rotherham-born Roy Harris made one of his return visits from his home in Anglesey in the late 70s, the closure of the Prince of Wales Power Station prompted him to contact the Advertiser.

He said: “This time the change was immediately apparent. Where once the twin cooling towers had dominated the view across the valley, now the opposite hill and its green surrounds were revealed.

“Where five gaunt business-like chimneys had seemingly forever supported their plumes — to the irritation of some and pride of others — now, only two stark mementoes remain.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“The sad truth struck, and I realised that if I was ever to revisit those scenes of earlier years, it would have to be now or possibly run the risk of never seeing it again.

“I was met by the two remaining watchdogs, who allowed me to take my time to wander through the maze of gantries and cold silent boilers to look along that once impressive row of turbines now at their final rest.

“It was all intact,” added Roy. “Every valve, hand-wheel, notice, motor, pump, fan, table and chair was there — everything except people.

“On this site, day and night, through wars and peace, a continuing series of struggles has been waged against temperamental plant, difficult fuels, and the capricious tendencies of a polluted river to keep the town and its industries supplied with electricity.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“With the aid of hindsight, it is a common practice to belittle the deeds of our forebears, but at least in the field of electricity supply, the town fathers built well and with vision.

“The station belonged to the town, and in its way, the town depended on the station.”